Common mistakes in the valuation of SMEs

How to recognise and avoid them

Business valuation is sometimes said to be more art than science. But even art requires craftsmanship. This article deals with frequently observed mistakes in the valuation of SMEs, how to recognise them and, of course, how to avoid them.

Every reader of r&c will have to deal with business valuations. Be it professionally or privately, be it as a valuer or expert, on the buyer’s or seller’s side. There are no special methods for the valuation of SMEs, but the special features of SMEs must be taken into account in the valuation.

With regard to the methods, valuation theory is unanimous: only future performance methods – capitalised earnings value or DCF methods – lead to “correct” company values. The practical method, which is widely used in practice, is controversial and is coming under pressure in case law. The current Expertsuisse business valuation bulletin also regards the DCF method as best practice. We also assume such a valuation here.

Wrong priorities

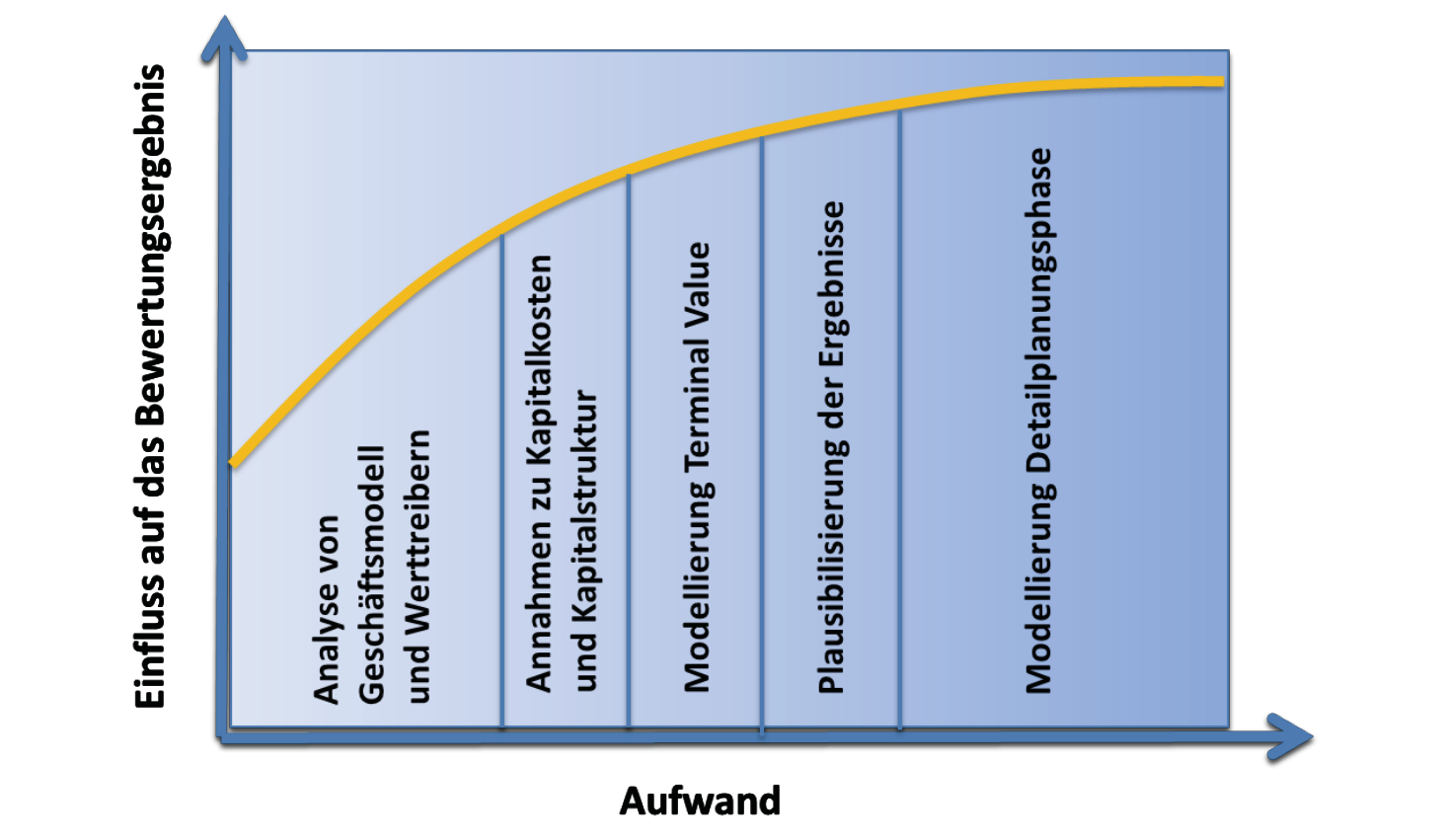

Company valuations are always time- and cost-critical events. All the more reason to do what is important and right quickly. Incorrectly set priorities are a major mistake in the valuation of SMEs, which can lead to significant misvaluations. Figure 1 arranges the work steps according to effort and relevance to results.

The illustration – admittedly based on anecdotal evidence – shows the problem: In business valuations, a lot of effort is spent on modelling the first three to five years, leaving little time for considerations of capital structure or residual value. It is well known that the residual value can easily account for 60 to 70% of the total enterprise value. It is therefore obvious that one should deal with it intensively. This will be discussed later.

The importance of the capital structure, on the other hand, is often underestimated. Assumptions about debt are necessary for the cost of capital. Often, blanket assumptions – such as 50% equity – are made without, however, being aware of the far-reaching consequences: With the assumption of a fixed capital structure, the cost of capital – and thus a key value driver – is fixed. Any further planning of the financing is also superfluous, since the capital structure is fixed. It is all the more important to justify the capital structure. This depends on the concrete valuation situation: In the case of purchase or sale, it is quite possible to base the valuation on industry values. When valuing minority interests, on the other hand, one will have to choose the actual capital structure, since a minority usually cannot influence the financing.

Read the complete article from the trade magazine rechnungswesen & controlling (r&c) 1|2018 (in German) here.